Ouch, My Balls! The Philosophy of Crank: High Voltage

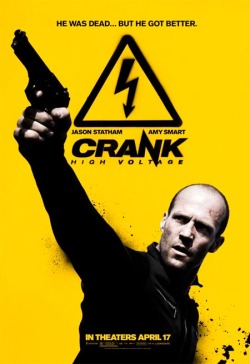

Crank: High Voltage is a visceral experience. It is so insane, so perverse, so racist and misogynistic, that it can only be one of two things. It's either one of the most despicable pieces of garbage ever filmed, or it’s actually an incredibly self-aware piece of subversive satire. This is a film that has been dismissed by critics as a fun B-level action flick at best, and a morally offensive junkyard at worst. But I think there’s a certain level of intelligence running through Crank 2’s orgy of debauchery. In fact, I would go as far to say that this is a film that’s going to be studied in film classes years from now, not as any sort of “classic” by any stretch of the imagination, but as a piece of quasi-avant-garde filmmaking that had its finger on the pulse of a generation.

I recently re-watched Crank: High Voltage with my parents, both of whom loathed the film and found it to be borderline pornographic in its depiction of women and violence. My mother said it was like a fantasy for white Southern “bubbas.” She’s absolutely right. Take the stereotypical image of a white trash, politically conservative male – the kind who idolizes guns, frequents strip clubs and still uses the n-word – and give that guy a video camera. This is probably what you’d end up with.

It’s easy to see why critics have called Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor (or Neveldine/Taylor as they’re frequently credited) misogynistic. For most of the film, they are. The camera moves effortlessly across flesh like a Hustler-produced music video. It’s shoved right up into cleavage and buttocks, so close you can see the individual skin pores. In the fantasy world of Crank 2, all women exist for sex. That is their one and only purpose. We find out that Chev’s girlfriend Eve has become a stripper since the first film. She never got the emotional message he left for her as he was supposedly falling to his death; Crank 2 isn’t about heart (ironically), it’s about cartoons. As they drive away from the strip club, one of Eve’s fellow strippers won’t stop pawing at her and trying to engage in some sort of lesbian encounter. The female characters seem incapable of functioning without being sexualized in some manner. And if they don’t act that way, they’re threatened with violence. Doc Miles (once again played by Dwight Yoakam), who in the first film was introduced getting a massage by two nude young Asians, now spends most of his free time with an African-American prostitute he at one point threatens to physically abuse if she doesn’t obey him.

The only exception to this rule is Eve. She spent the first film acting as Chev’s sexual adrenaline provider. It’s a role she continues to serve in this film until she is once again left alone after a public sex scene. Then it becomes apparent that Neveldine/Taylor are well-aware of how they’re presenting women in the film, and they’re doing it for a reason. They’re taking a staple of action films and video games – a love interest who serves only to meet the needs of the hero – and blowing it so far out of proportion that it becomes farce. What is a public sex scene if not a metaphor for how women are often treated in cinema itself, as mere sex objects to gratify thousands of strangers? She angrily stomps away from the scene, humiliated. When her new boyfriend-slash-pimp threatens to “drop the hammer” if she doesn’t do what he wants, she beats the crap out of him. Suddenly, she isn’t just a cardboard cut-out of a character anymore. She’s starting to become an individual.

If you still aren’t convinced that Neveldine/Taylor have some idea of what they’re doing, just take a look at the last scene dedicated to Eve. She’s at a police station being interrogated by a policeman, who describes how Chev has brought her nothing but harm and humiliation. He cuts straight to the heart of the matter: “Why the fuck do you continue to protect this asshole?” She responds, “That’s a dicky question. I’d like to see you fall out of a helicopter…” She is with him because he is Superman. The implication is clear: this is a fantasy, nothing more. Don’t think you can treat women like this in real life and get away with it.

But make no mistake about it, this isn’t a film about women as much as it’s a film about men and male fantasy. There’s a reason why the dominant image of the film is male genitalia. This is a movie about hyper-masculinity. In the first film, Chev Chelios was an action hero, but he was still a man. In the sequel, he’s a force of nature. From the very first scene it’s made clear that this isn’t a film set in “the real world,” but a video game fantasy land where our hero can literally “power up,” women are sex objects, and men are gods.

Within the first 30 seconds of the film, Chev goes from being a hitman with an unusual penchant for dodging bullets to full-on immortal. He’s survived a fall from several thousand feet. As his heart is removed by Chinese gangsters and replaced with a mechanical one, he watches the proceedings with an expression not of pain, but mere annoyance. He’s no longer human. He’s caricature. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a 1-Up mushroom. Whereas the tension in the first film came from not knowing if he’d be able to survive, the tension in the second film comes from not knowing what crazy thing a man who can’t be killed is apt to do. The possibilities are endless, and that Neveldine/Taylor find a way to constantly up the ante with each subsequent scene is a testament to the scope of their imagination (and arguably of their depravity). We can only be dragged along for the ride.

Chev Chelios is machismo taken to the extreme. By electrically shocking his body (the film’s equivalent of eating a Mario Brothers mushroom), he becomes so strong that he can fight off dozens of opponents at once, or dash from one part of the city to another in a matter of seconds. He also apparently has a penis the size of a small limb. I mean, he wouldn’t be a true man otherwise, right? The other characters can only try to be as much of a man as Chev Chelios. At one point in the film, a Hispanic gang member is forced to chop off his own nipples. Anything remotely related to femininity, even physical anatomy, must be vanquished in the pursuit of unadulterated male power.

But just as the character of Eve begins to overturn the film’s objectification of women, there are several sequences which suggest Crank: High Voltage isn’t meant to be viewed as a male fantasy so much as a male nightmare. Are you a man who likes his penis? If so, you might want to avoid this film, because it contains more genital mutilation than an evening with Bob Flanagan. Chinese gangsters discuss a plan to amputate Chev’s extremely large member. Bai Ling bashes in a man’s groin with a bicycle. The villain’s name is The Ferret, and introduced with grainy footage of a ferret scratching its balls. At the end of the film, Chev is tortured by electro-shocking his testicles, which are shown in close-up.

There are too many scenes of genital smashing for it to be a coincidence. I believe this was intentional. Neveldine/Taylor are poking fun at notions of masculinity by taking larger-than-life maleness and literally kicking it in the balls. While female anatomy is sexualized, male anatomy is either mutilated or a source of humiliation. Not only that, but at one point in the film Chev receives such a powerful charge of electricity that he literally becomes a giant, Godzilla-esque puppet. He has become so hyper-macho that he’s a deformed parody of himself. And then there’s a scene where Glenn Howerton (from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia) is in therapy due to the events that occurred in the first film, but as soon as he starts to get excited about living life again (specifically by the prospect of “getting his dick wet”) he is killed by a bullet ricochet. It could be argued that this is his punishment for being such a sexist, or his therapist’s punishment for acting as a seductress rather than a caring human being.

And yet, aren’t Neveldine/Taylor just critiquing gender roles that are present in most mainstream media nowadays? It’s no secret Neveldine/Taylor like video games and incorporate video game culture into their films. Each of the Crank films opens with a short 8-bit graphic. At one point in the first film, Chev mentions that his public alias was a video game programmer. There’s also a shot of a character playing an old 8-bit game called Berzerk – interestingly enough, this is a game that has indirectly contributed to the death of two teenagers. The duo are also responsible for last year’s Gamer, which starred Gerard Butler as a man whose body is literally controlled by a video game player. Clearly, Neveldine/Taylor are aware of the complex relationship that exists between the “imagined life” of fiction and the “real life” in which we live. They’ve heard the complaints that video games (and perhaps movies such as their own) can inspire violence, and they want to examine that relationship while still making a balls-to-the-wall action thrill ride.

There is a flashback scene in Crank: High Voltage that serves no purpose except to bring up these issues. Why other critics haven’t jumped all over this scene is beyond me, since it’s in many ways the thematic core of the film. Chev has a flashback to when he appeared on a Maury-esque talk show as a child, complete with a little label that describes him as “Chev Chelios: Youth Destined For Damnation.” The host talks to him and his mother about his violent tendencies and his life at home. The exchange is as follows:

Host: Tell me what he’s like when he’s at home.

Mother: When he’s at home, he’s like a ghost. He just plays those video games all day and all night.

Host: And you let him do that? I mean you did buy the games for him, yeah?

Mother: Of course. Why should I deny my son?

This leads into a description of the violent acts and illegal activities Chev has been involved in, followed by:

Host: Chev, where’s Dad?

Chev: I never met the wanker. He died before I was born.

Host: What do you think he’d say if he saw you acting out like this?

Chev: I don’t know, sir.

Host: If he were here now and he asked you, “Why the hell do you do the bloody things you do, son?” what would you tell him?

Chev: Don’t know, sir. Bored I guess.

Boredom. That’s the real villain of the film, not some stereotypical cartoon mastermind. And while you may finish the movie feeling extremely offended, at least you won’t be apathetic. After all, that might lead you to go out and cause some real damage.

Crank: High Voltage may be a hillbilly fantasy, but it’s not meant to be taken seriously. If anything, it’s meant to be mocked and laughed at. Pick up a copy of Grand Theft Auto or a James Bond film and you’ll find the same ideas. Men are macho heroes, and women are their sex slaves. Perhaps it says something about the filmmakers’ philosophy if, at the end of Crank and Crank: High Voltage, Chev is only able to defeat the bad guys after receiving help from the ethnic minorities, strippers, and homosexuals that are frequently the butt of jokes. At the end of the day, he’s the one on fire, burning himself and everyone around him as he literally breaks the fourth wall and flips the world the bird, just as he did to the talk show audience as a child. He’s a broken man full of anger, not a hero but someone to be pitied.

If Crank was a live-action video game, Crank: High Voltage is a subversion of common video game tropes and stereotypes. It takes its stereotypes to such cartoonish extremes that arguably it deflates them and exposes their true emptiness. It is essentially nothing more than a loose collection of sketches held together with a paper-thin plot, each designed to be more outrageous than the one before it. Why? Because Neveldine/Taylor want to push the envelope of taste, yes. But I don’t think it’s simply “shock for shock value,” as some critics have complained. It’s a film that realizes it is a film, a piece of media to be consumed by mass audiences, and it’s interested in exploring the effect that media violence has on culture and what twisted impulses are satisfied (or not) by watching someone like Chev Chelios do his thing.

Things To Think About: Is enjoying a film like Crank: High Voltage the same as agreeing with its prejudiced ideas and stereotypes? Even if Neveldine/Taylor wouldn’t actually advocate racism/sexism and are in fact trying to subvert these ideas, does the sheer amount of offensive material undermine their attempt? What is the relationship between video game and player, film and audience? Which is actually projecting their own values on the other?