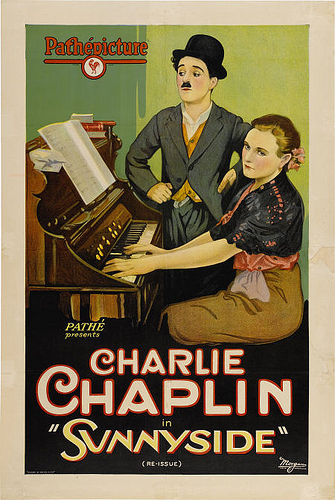

The Chaplin Chapters: Sunnyside (1919)

Sunnyside was Chaplin's third film for First National Pictures. Although it received mixed reviews upon its released and was somewhat of a commercial disappointment, it still contains some solid gags, and is noteworthy for having what is arguably the most depressing ending in Chaplin's major filmography.

The plot finds Chaplin playing a farm handyman who also looks after the village hotel. He is introduced as such by a title card that is either one of the laziest title cards ever written, or a brilliant jab at the way many of them are composed: "Charlie the farmhand, etc. etc. etc." The opening scene finds him unwilling to get out of bed early in the morning, despite efforts by his boss to get him off to work. When he finally makes it downstairs to prepare breakfast, he gets it directly from the source. There are a variety of gags in this scene, most of which work, whether it's him waiting impatiently for a chicken to lay an egg or getting milk straight from the cow.

When he heads off to town, a fascinating title card pops up that establishes nature as Chaplin's religion of sorts: "His church, the sky -- his altar, the landscape." He's most fulfilled when working outside. This leads into another scene in which he loses a herd of cows, only to ultimately have to chase down a bull. The townspeople run after him, and he unfortunatedly falls off a small bridge and is knocked unconscious. This leads to a staple of Chaplin's early work: a dream sequence, which finds him frollicking carefree with a group of beautiful women through open fields. This is the happiest he'll ever be in the film (and arguably in any of his work), free to enjoy nature with people who might satisfy his loneliness. Unfortunately, like all things that are too good to be true, he must eventually wake up from the dream and rejoin reality.

However, the potential for happiness still exists - Charlie's in love! He pines for a local woman in town (once again played by Edna Purviance - one begins to wonder if Chaplin ever really got over her), and attempts to woo her at her house with comical results. Unfortunately, a wealthy city slicker is in a car crash and winds up spending a few nights as the hotel to recover. Edna catches his eye, and romance seems inevitable. Desperate to win her heart, Charlie tries to dress in more sophisticated-looking attire and act like a member of the upper-class. It's a gamble that ultimately fails when, at her home, his costume starts to comically come undone.

In a fascinating twist, however, the comedy is quickly replaced by overwhelming pathos. The ending to Sunnyside is one of the darkest and most pessimistic I've ever seen, and caught me completely off guard. Having ultimately failed to win back the love of his life, Chalin's handyman runs outside and straight into the path of an oncoming car. There's a quick dissolve to another scene: Chaplin and his love, now married and living happily ever after. Some argue that this implies the previous show is nothing but a close call; the car ultimately missed him and he was able to achieve his goals. However, I think that's a rather naive and highly optimistic interpretation that doesn't complement the overarching themes of Chaplin's work. The last scene is clearly a fantasy sequence that occurs in the moment of his death/suicide - another depressing and cynical use of a dream sequence, similar to that utilized in Shoulder Arms. Facing a life largely apart from nature with continued forced labor on behalf of his boss, and without a special someone to return home to at night, he chooses to die, with nothing but the dream of a fantasy life left to comfort him in the moment of death.

This ending cements Sunnyside as a key work in Chaplin's oeuvre, despite the fact that it's arguably not as consistently entertaining and funny. With it, he continues to establish themes that will characterize his filmography: the futility of attempting to rise above one's class, the difficulty in finding personal fulfillment in a society that demands constant hard physical labor, and the conflict between reality and the dream that the working class is encouraged to adopt. One could easily argue that this is a film in which Chaplin's leftist political leanings are most apparent, with comedy being used to gather sympathy for what is ultimately a rather Marxist depiction of the trials and tribulations of the proletariat. Regardless of whether or not this is in fact the case, it's a fascinating portrayal of how the harsh reality of working class life can frequently provoke delusions of grandeur that ultimately are left unfulfilled.