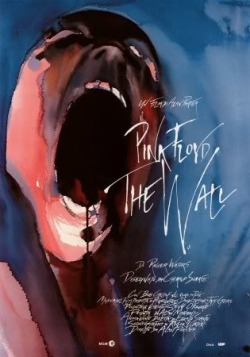

Review: Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982)

Are you:

Are you:

a) a fan of good music,

b) someone who doesn’t automatically dismiss any film described as “artsy,”

c) a consumer of hallucinogenic and psychedelic substances, or

d) a tortured soul consumed by angst and searching for your place in the universe?

If you answered “yes” to any of those, you’ll probably like The Wall, the 1982 musical film based around the Pink Floyd album of the same name. And if you answered “yes” to all four, it could potentially become one of your all-time favorite films - the cinematic equivalent of manna from heaven.

To call this film “trippy” would be like calling water wet. Rather than a concert film, viewers are thrust into a chaotic montage of scenes and images that, while communicating a loose narrative, serve mainly to reflect abstract themes and emotions. In his review, Roger Ebert claims it’s more like a 95-minute music video than a performance piece. He’s correct. The separate scenes associated with each song each illustrate the primary difference between music videos and narrative filmmaking: the emphasis is more on crafting an overall sensory experience than telling a coherent story. Whereas in most mainstream films, music is frequently only used in the background to add weight to the imagery, here the imagery is meant to fully communicate the soundtrack.

And oh, what a soundtrack. Until viewing this film, I was convinced that Pink Floyd was one of the most overrated rock groups of all time. While I could tolerate a few of their more well-known songs, I usually found their use of synthesizers and electronic effects to be off-putting. After seeing The Wall, I now realize that what made their music so popular and groundbreaking was not the quality of the lyrics or the catchiness of the melodies, but the hypnotic and angst-driven quality of the instrumentation. These are not songs meant to be sung in the shower. These are songs that come from a very dark and fractured place, and were very personal to primary songwriter Roger Waters. When listened to in conjunction with the other tracks, each piece feels like one step in a larger thematic journey. They are like memories, not always fully understandable on a literal level, but always relatable in an experiential sense. When combined with the cinematography of director Alan Parker and the cartoons of Gerald Scarfe, the abstract nature of the music is enhanced and, I would argue, improved. Though it’s not a concert film, The Wall achieves what most concerts strive to be: a richer and fuller expression of the music. Instead of strobe lights, flame jets and set pieces, we’re presented with dissolves, overlays and animation.

And oh, what a soundtrack. Until viewing this film, I was convinced that Pink Floyd was one of the most overrated rock groups of all time. While I could tolerate a few of their more well-known songs, I usually found their use of synthesizers and electronic effects to be off-putting. After seeing The Wall, I now realize that what made their music so popular and groundbreaking was not the quality of the lyrics or the catchiness of the melodies, but the hypnotic and angst-driven quality of the instrumentation. These are not songs meant to be sung in the shower. These are songs that come from a very dark and fractured place, and were very personal to primary songwriter Roger Waters. When listened to in conjunction with the other tracks, each piece feels like one step in a larger thematic journey. They are like memories, not always fully understandable on a literal level, but always relatable in an experiential sense. When combined with the cinematography of director Alan Parker and the cartoons of Gerald Scarfe, the abstract nature of the music is enhanced and, I would argue, improved. Though it’s not a concert film, The Wall achieves what most concerts strive to be: a richer and fuller expression of the music. Instead of strobe lights, flame jets and set pieces, we’re presented with dissolves, overlays and animation.

Our protagonist is a rock star named Pink, and the stage is his psyche. Through the course of the film we’re introduced to various “bricks” in the wall that symbolizes both his self-imposed isolation and the essence of his self. We see his father, killed in the war. We see his mother and wife, oppressive figures that in some of the film’s most disturbing sequences seem to literally emasculate him. We see the school he attended as a child, and the teachers that encouraged psychological and social conformity. And finally, we see his career, as he visualizes himself not as merely a rock star but as a perpetrator of the very fascism he’s come to detest.

Our protagonist is a rock star named Pink, and the stage is his psyche. Through the course of the film we’re introduced to various “bricks” in the wall that symbolizes both his self-imposed isolation and the essence of his self. We see his father, killed in the war. We see his mother and wife, oppressive figures that in some of the film’s most disturbing sequences seem to literally emasculate him. We see the school he attended as a child, and the teachers that encouraged psychological and social conformity. And finally, we see his career, as he visualizes himself not as merely a rock star but as a perpetrator of the very fascism he’s come to detest.

It’s a story of angst, despair and a desperate search for meaning. One gets the sense that when writing it Roger Waters was questioning not just his existential purpose but everything: the building blocks of society, economics, and psychology. Moreso than the majority of films, this is a movie that takes a look at not merely a single linear plotline, but the very essence of the human experience. It’s an exploration of the Self, how it’s formed and whether or not it’s truly possible to escape socialization. Is independence even possible, or are we all forever doomed to be slaves to outside systems and experiences? The Wall doesn’t try to document the answer, just the search for one, with all of its madness and ambiguity. At this it succeeds admirably.

This is neither a typical concert film nor a typical narrative film. It is a unique hybrid of both, utilizing the techniques of each to create something that is extremely personal while exploring ideas and questions that are universal. While the dark subject matter doesn’t make The Wall a film that demands to constantly be revisited, it should be at least be seen once. It’s certainly not for everyone, but at the very least it has a good soundtrack. Indeed, perhaps the ultimate sign of its power is that now, instead of changing the station every time a Pink Floyd song comes on the radio, I can’t help but be drawn into the music.